A New Hollywood

In the late 1960s and early 70s, a new generation of young filmmakers came to prominence in American cinema. Their work was thematically complex, formally innovative, morally ambiguous, anti-establishment, and rich in mythic resonance. They spoke for a generation disillusioned by the Vietnam War, disenchanted by the ruling elite, and less willing to conform than their parents.

Dubbed the "New Hollywood" by the press, their films were mostly financed by the major studios, but they introduced subject matter and a new stylistic approach that set them apart from studio tradition. Influenced by the revolutionary new waves of cinema coming out of Europe, they re-worked, and re-imagined, some of Hollywood’s classic genres – such as the crime film, the war film, and the western – and by doing so, presented a more critical view of America, past and present.

In front of the camera, a brilliant new generation of actors and actresses, often trained in acting schools in New York, brought a new level of realism and intensity to the screen. While behind the scenes – writers, cinematographers, editors, composers, and other creative figures – changed the way American movies looked and sounded.

Although the new generation’s ambition to overturn the system and create something better in its place may have ultimately failed, they did succeed in producing a body of work now considered a golden age in American cinema.

Barbarians At The Gate

Cleopatra [1953]

|

In the years following the Second World War, the major film studios had lost much of their once unassailable power. As a result of the Paramount Antitrust case of 1948, they lost the right to own their own theatres, as well as exclusive rights on which theatres would show their films. Consequently both their revenue and influence declined.

The studios were weakened further by the popularity of television in the 1950s. Their response was to offer audiences something they could not find elsewhere: Technicolor, widescreen, stereo sound, and 3-D. Historical epics and musicals – the genres that most suited these innovations – dominated production. In the 1950s the strategy paid off with major box office successes like The Ten Commandments (1956), South Pacific (1958), and Ben-Hur (1959) keeping the Studios in profit, but by the 1960s production costs were escalating and audience tastes had begun to change. Twentieth Century Fox’s production of Cleopatra (1963) ran disastrously over budget and the film was unable to recoup its costs at the box office, almost bankrupting the studio as a result. The still popular family musical reached the peak of its popularity with My Fair Lady (1964) and The Sound of Music (1965), but thereafter its appeal began to wane. Old Hollywood was losing both money and audience share at an alarming rate, and the aging studio bosses, out of touch with the tastes of the new baby boomer audience, were at a loss as to what kind of films they should now be making.

Blow Up [1966]

|

For many in America at that time, the most exciting films in the cinemas were imports from abroad. The success of British films such as Alfie, Georgie Girl and Blow Up, all released in 1966, showed audiences were ready for more sexually explicit content, looser narratives, and soundtracks featuring contemporary rock music. Urban cinephiles, and the first generation of film students, waited expectantly for the latest work by such celebrated foreign auteurs as Ingmar Bergman (Sweden), Akira Kurosawa (Japan), Frederico Fellini (Italy), Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard (France).

Meanwhile, as the once celebrated movie moguls died or retired from the business, so the studios began to be bought up and taken over by huge business conglomerates. Film production became a sub-division of companies otherwise involved in selling such commodities as insurance, cars, sugar, mining, records and real estate. However, the upheavals at the studios also provided opportunities for new heads of production and young executives who were more willing to take risks than their predecessors. They realised that the audience’s cinematic appetite had changed and were ready to back projects and filmmakers who could cater for it. The time of the American New Wave had come.

1967

Though the year 1967 is now often cited as a turning point in the history of American cinema, few working in the film industry at the time were aware of it. The major studios continued to put most of their resources into the kinds of movies that had proved successful in the past, which meant big budget musicals like Camelot (Warner Brothers) and Dr Dolittle (20 Century Fox); James Bond spectaculars (United Artists) and their spoof offspring like Our Man Flint and Casino Royale; and middle-of-the-road star vehicles such as Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (Columbia). Many working in the industry knew that most of the mainstream Hollywood output was mediocre, but few were willing to risk their careers by opposing the wishes of the studio heads.

In The Heat of the Night [1967]

|

Yet, despite their innate conservatism, the studios had begun producing films whose depictions of violence, sex, and drug taking would not have been possible just a few years before. The appointment in 1966 of Jack Valenti as the new head of the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) had resulted in an overhaul of the outmoded Production Code, allowing a new level of freedom in what could be shown on screen. Perhaps more significantly, some of the biggest hits of the year, including The Dirty Dozen, Cool Hand Luke and Oscar-winning race drama In the Heat of the Night, were all defiantly anti-authoritarian in a way that appealed to the younger, twenty-something audience that had been largely ignored by Hollywood in recent years. But it was two new films in particular, Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, that, with hindsight, make 1967 such a significant year in American cinema. Rebellious in spirit and creatively adventurous, their unexpected box office success and wider cultural impact made them the progenitors of the New Hollywood revolution.

“They're young, they're in love, they kill people."

Jean-Luc Godard's Alphavile

|

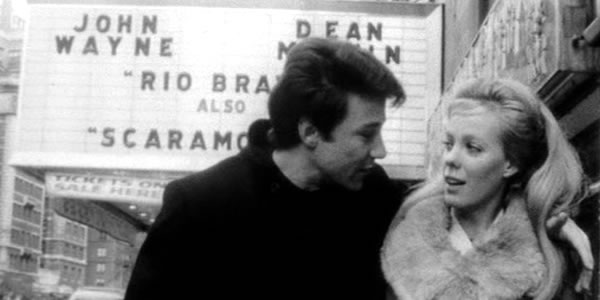

In 1963 Robert Benton and David Newman were two young writers working for Esquire magazine in New York, when they first had the idea to write a screenplay based on the Depression-era gangsters Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Although, by their own admission, they knew very little about scriptwriting, they wrote what they wanted to see, and the result was a fresh new perspective. They were influenced, not by classic American cinema, but by the films then coming out of Europe, particularly those of the French New Wave. Their heroes were Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, and in their script they sought to emulate the audacious cinematic technique and moral ambiguity of Godard’s Breathless (1960), and Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1961). For a time, first Truffaut, then Godard, were attached as potential directors of the film, but both dropped out to work on other projects.

Warren Beatty first heard about Bonnie and Clyde when he met Truffaut while on vacation in Paris. The French director recommended he read the screenplay, so on his return to NewYork he called on Benton and Newman and asked for a copy. An hour later, still only half way through reading it, he called them and said he wanted to option it. And not only did he want to play the lead part, he wanted to produce the film as well.

Beatty reportedly begged Jack Warner, the aged head of Warner Brothers, on his hands and knees to finance Bonnie and Clyde. A reluctant Warner finally agreed to the relatively low budget of $1.6 million. There was little enthusiasm either from directors, who, one after another, turned the project down. Benton and Newman suggested Arthur Penn whose film, Mickey One (1965), also starring Beatty, had first introduced French New Wave style cinematography and editing to American cinema. Penn, though, who had made his name directing live television in the 1950s and was nominated for an Oscar for directing The Miracle Worker (1962), was reluctant to make another Texas-set crime story after the difficulties he had experienced making The Chase (1966) with Marlon Brando. However, after researching the true story of the crime duo he found something that captured his interest, as he later explained to author Mark Harris: “I had seen it as this romantic legend all the way through. But then I thought, this is really a story about the agricultural nature of the country. Those banks they robbed were farmers’ banks, and then the farmers couldn’t pay their mortgages, and eventually the banks took over the farms… Well, all of that was not in the script. But I thought it could be.”

Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde [1967]

|

When Jack Warner first saw a rough cut of Bonnie and Clyde in the summer of 1967, he hated it. Distribution executives at Warner Brothers agreed, giving the film a low-key premiere and limited release. Their strategy appeared justified when Bosley Crowther, middle brow film critic at The New York Times, gave the movie a scathing review. “It is a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy,” he wrote, “that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cut-ups in Thoroughly Modern Millie…” Other notices, including those from Time and Newsweek magazines, were equally dismissive.

Then, beginning with Pauline Kael’s nine thousand word rave review of the film in The New Yorker, critical opinion began to change. Time put a still from the film on the cover to illustrate an article by Stefan Kanfer entitled: “The New Cinema: Violence… Sex… Art”. The piece called the film “the best movie of the year,” a “watershed picture,” and bracketed it alongside The Birth of a Nation and Citizen Kane as the groundbreaker of its era. This coincided with the film’s popularity with a younger generation of moviegoers who identified with the protagonists’ rebellious spirit. At Beatty’s urging, the film reopened in American cinemas and quickly took off, becoming one of the biggest hits of the year. The final seal of approval came when it was nominated for ten Academy Awards (it won two – Best Supporting Actress and Best Cinematography – at the 1968 ceremony).

“This is Benjamin. He’s a little worried about his future.”

Bonnie and Clyde wasn’t the only trailblazing new film released in 1967. Mike Nichols’s The Graduate, though ostensibly a comedy, spoke for a disaffected younger generation who had begun to question the mores of their parents’ generation. Its story, adapted from a novel by Charles Webb, tells of Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), a directionless college graduate who is seduced by an older woman, Mrs Robinson (Anne Bancroft), only to fall in love with her daughter Elaine (Katherine Ross). The rights to Webb’s 1963 novel had been optioned by producer Lawrence Turman soon after the book came out, but he had been turned down by every major studio, despite having Mike Nichols, highly acclaimed for his work in the theatre in New York, signed on as director. Nichols had originally planned The Graduate as his film directing debut, but frustrated by the delays in financing, agreed instead to accept an offer from Warner Brothers to direct a screen adaptation of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor at the height of their celebrity, the film was a huge hit, grossing $14.5 million and winning five Academy Awards with thirteen nominations. This was enough to convince Joseph E Levine, the maverick head of independent production company Embassy Pictures, to provide financing for The Graduate.

Mike Nichol's The Graduate [1967]

|

From the start Nichols made audacious creative choices for The Graduate that went against orthodox filmmaking practices of the time, but which would ultimately prove inspired and fundamental to the film’s success. The first was to throw out an earlier, more orthodox draft of the screenplay by established screenwriter Calder Willingham, and to hire comedy writer Buck Henry, previously known for his theatre and TV work, to write a new adaptation from scratch. When it came to casting the role of Benjamin Braddock, Nichols cast against type, choosing an unknown 29-year-old Jewish New York-based theatre actor Dustin Hoffman, rather than the tall, blond, blue-eyed Robert Redford, who wanted to play the part and seemed much closer to the character described in the novel. Nichols was equally innovative during production, pushing veteran cinematographer Robert Surtees to experiment. “We did more things in that picture than I ever did in one film,” Surtees later wrote. During post-production, Nichols interspersed a traditional musical score by Dave Grusin, with songs by the then little-known folk-rock duo, Simon and Garfunkel, an unusual approach at the time, but one which would contribute greatly to the film’s impact.

When it was released in the final weeks of 1967, The Graduate was received with mixed reviews. Time magazine dismissed the film as “alarmingly derivative and … secondhand”, while Pauline Kael described Nichols’s direction as a “bad joke”. Perhaps surprisingly, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, who had so hated Bonnie and Clyde, gave the movie a rave. “Benjamin Braddock,” he wrote, “is developed so wistfully and winningly by Dustin Hoffman, an amazing new young star, that it makes you feel a little tearful and choked-up while it is making you laugh yourself raw”. Some older critics admitted they didn’t understand the film’s appeal. Writing in Ladies’ Home Journal, David Brinkley called the movie “frantic nonsense” but admitted that his collage-age son and his friends “thought The Graduate was absolutely the best movie they ever saw… they liked it because it said about their parents and others what they would have said about us if they had made the movie – that we are self-centered and materialistic, that we are licentious and deeply hypocritical about it, that we try to make them into walking advertisements for our own affluence.”

Cinemagoers took little notice of the negative reviews and flocked to see the movie, turning it into one of highest-grossing motion pictures of 1968. Like Bonnie and Clyde it also received multiple Academy Award nominations (seven in total). The film’s success was so categorical that Warner Brothers and United Artists announced that they were rethinking their entire development slates with a view to appealing to younger audiences. The other studios soon followed their example.

The unexpected critical and box office success of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate showed that the public were ready for something new. The Second World War baby-boom generation, nurtured on rock and roll and the immediacy of television, had now come of age. More inclined to be suspicious of authority and an Establishment who had dragged America into yet another war, they identified with anti-heroes who rejected the status quo. The fact that both Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate had been so difficult to finance demonstrated that the studios had lost all sense of what the public wanted to see. Chastened by their misjudgement, they now began opening their doors to younger filmmakers more in tune with the concerns of the newly evolving youth audience.

Immigrants and Exiles

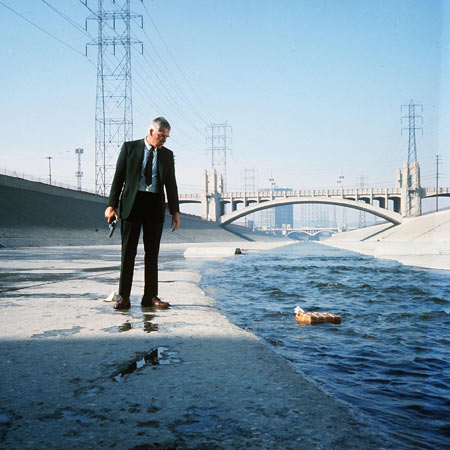

Boorman's Point Blank [1967]

|

Among those who would have the greatest impact on the style and tone of the new American cinema were European emigrees like British director John Boorman.

His previous work included television documentaries for the BBC, and the Dave Clark Five vehicle, Catch Us If You Can (1965). “There was a complete loss of nerve by the American studios at that point,” Boorman said in a later interview. “They were so confused and so uncertain as to what to do, they were quite willing to cede power to the directors. London was this swinging place, and there was this desire to import British or European directors who would somehow have the answers.” Boorman was drawn to Hollywood for the opportunity to make larger scale cinema. In his first American feature, Point Blank (1967), he used elliptical editing, tonal ambiguity, and an expressionistic use of colour and widescreen to stunningly reinvent the film noir genre.

Polish director Roman Polanski, signed to Paramount by its new head of production Robert Evans, was a man of persuasive charm and exceptional talent. His first feature, Knife in the Water (1962), made soon after he graduated from the famous Polish national film school in Lodz, received international acclaim and a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Moving to England, he made three more distinctive films, including the disturbing, but brilliant, Repulsion (1965). Polanski’s American debut, Rosemary’s Baby (1968), was his best and most popular work yet. Telling the story of a satanic conspiracy set in a hotel in New York, its menacing atmosphere, urban paranoia, and dark sense of humor brought a hip new sensibility to the horror genre.

Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968]

|

Boorman, Polanski, and other British and European immigrants like John Schlesinger and Milos Foreman, would contribute some of the best work of the New Hollywood era. They brought with them from their homeland an outsider’s perspective and a bold approach to film technique. Their work explored the contradictions of America life, revealing not only its beauty and vitality, but also the moral corruption lying so often beneath the surface.

Taking the opposite course to his European counterparts by moving to England in 1962, American director Stanley Kubrick had exiled himself intentionally from the power machinations of Hollywood. In the late 1950s and early 60s, Kubrick had established himself as a fiercely independent filmmaker with a unique vision and a brilliant command of technique. His ingenious heist drama, The Killing (1956), brought him to the attention of MGM, for whom he made the critically acclaimed WWI war film Paths of Glory (1957). He replaced Anthony Mann at the last minute to direct Spartacus (1960), but found the experience a difficult one. He vowed to never to work on another film on which he did not have absolute control and made his next two films, Lolita (1962), and Dr. Strangelove (1964), in England, far away from the interfering control of the Studios. While making his next film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Kubrick settled in England permanently.

2001, devised in collaboration with writer Arthur C. Clarke, was not only a quantum leap forward for the science-fiction genre, but redefined the parameters of the cinematic experience altogether, becoming, after a slow start, one of 1968’s biggest hits. Steven Spielberg later described the film as “the big bang of his generation”, and it’s hard to imagine later works such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Star Wars (1977) without it. For the New Hollywood generation of directors, Kubrick’s artistry and status as an auteur – financed by the Hollywood studios but independent of their interference – was an ideal to aspire to.

King of the Bs

Roger Corman's The Trip [1967]

|

Roger Corman was another successful independent filmmaker. Since the mid-50s, he had successfully cornered the market in exploitation teen flicks, cheap sci-fi and horror. The major studios may have felt that movies like Sorority Girl (1957) and The Wasp Woman (1960) were beneath their dignity to produce, but such films fit the atmosphere of rural drive-in and inner-city Grindhouse perfectly, and Corman’s prolific output regularly returned a profit. Working for independent production company, American International Pictures, Corman directed such cult classics as A Bucket of Blood (1959), Little Shop of Horrors (1960), and his well-regarded cycle of Edgar Allen Poe adaptations that included House of Usher (1960), and The Pit and the Pendulum (1961).

Always quick to spot new talent, Corman was unafraid to offer opportunities to untried talent, as long as they didn’t expect too much in the way of a salary in exchange. One of his first protégés was a student from UCLA’s filmschool named Francis Ford Coppola. Coppola’s first job for Corman was dubbing and re-editing a Russian science fiction film Nebo Zovyot, which he transformed, with the addition of specially shot scenes of fighting space monsters, into Battle Beyond the Sun (1962). Impressed by Coppola’s perseverance and commitment, Corman hired him as the sound man on The Young Racers (1963). When the film came in $20,000 under budget, Coppola persuaded Corman to let him make a low-budget horror movie with the left over funds. Corman agreed on the condition he make a cheap Psycho-style thriller with a gothic atmosphere and plenty of bloodshed. Coppola seized the chance to direct his first feature. He wrote a screenplay overnight and directed the film, Dementia 13, in just nine days in Ireland.

Peter Bogdanovich directs Boris Karloff in Targets [1968]

|

Coppola returned to UCLA, and in 1965 won the annual Samuel Goldwyn Award for best screenplay (Pilma, Pilma) by a UCLA student. On the strength of this accolade, he was hired as a screenwriter by independent production company, Seven Arts, where he worked on scripts for This Property is Condemned (1966) and Is Paris Burning? (1966). Still desperate to make his name as a serious director, Coppola bought the rights to the David Benedictus novel You’re a Big Boy Now, and persuaded Seven Arts, who had now merged with Warner Brothers, to finance it. Telling the story of a sexually inexperienced 19-year-old named Bernard (Peter Kastner), suffocated by parental control, who works in the New York Public Library and longs for freedom and a girlfriend, the film’s frenetic, absurdist style resembled the work of Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night; The Knack …And How To Get It), but with little of the charm. Nevertheless, You’re a Big Boy Now received some good notices and was selected for competition at the 1967 Cannes Film Festival. At the age of 28, Coppola was already a legend among other film students for having broken through into the real world of film production. There would, however, be a few more faltering steps before he would establish himself as an important director in Hollywood.

Peter Bogdanovich was another aspiring filmmaker who got his first break working for Roger Corman. Born and raised in New York City, Bogdanovich was an obsessive cinemagoer from a young age. In his early twenties he got a job as a film programmer for the Museum of Modern Art, and began writing about cinema, publishing articles in Esquire, and monographs on Orson Welles, Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock. Inspired by the example of Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and the other French Cahiers du Cinéma film critics who had become important filmmakers in their own right as part of the French New Wave, Bogdanovich decided to become a director. He moved with his wife, production designer Polly Platt, out to Los Angeles, where, at a screening of Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961), he met Roger Corman. Corman, who had liked Bogdanovich’s articles for Esquire, hired him to work as production assistant on The Wild Angels (1966), as well as scriptwriter and second unit director.

Following the movie’s success, Corman rewarded Bogdanovich with the chance to direct a feature – the only stipulation being that he come up with a story that could include twenty minutes of outtakes from an earlier film, The Terror (1963), as well as a part for Horror legend Boris Karloff, who owed him two days work. Bogdanovich’s inspiration was to interweave the story of an aging, disillusioned horror movie star, played by Karloff, who believes that the violence of the contemporary world is making his old-fashioned horror redundant, with that of a young Vietnam War veteran who goes on a shooting rampage. This character was based on Charles Whitman, a student at the University of Texas, who shot and killed 16 people, including his wife and mother. Released in 1968, soon after the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Targets was an electrifying debut that demonstrated the young director had learned well from masters like Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock. The film’s exploration of the blurred line between real and fictional violence was brilliantly realised and gave notice of a promising new talent.

By offering opportunities to untried directors, Roger Corman played an important role in the modernizing of American cinema. Operating within the restrictions of budget and genre, the filmmakers under his charge had considerable freedom to introduce startling avant-garde techniques and unconventional messages. In addition to Coppola and Bogdanovich, he would help to launch the directorial careers of Dennis Hopper, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, and Jonathan Demme, as well as actors such as Jack Nicholson, Bruce Dern and Robert De Niro. All would go on to become key figures in the New Hollywood cinema of the 1970s.

“A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere…”

Mickey Dolenz of The Monkees in Head [1968]

|

Roger Corman wasn’t the only producer working in Hollywood with his finger on the pulse of youth culture. Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, both originally from the East Coast, met in the early 1960s while working in television and soon after formed Raybert Productions. Inspired by the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night (1964), the pair decided to develop a television series about a fictional rock and roll group and succeeded in selling the idea to LA based production company Screen Gems.

The first episode of The Monkees aired on September 12th 1966 and the show soon became a big hit. Its success provided Rafelson and Schneider with the opportunity to break into producing movies. Their first film, Head (1968), directed by Rafelson, produced by Schneider, and written by a then little known B movie actor named Jack Nicholson, featured the The Monkees in a psychedelic, stream-of-consciousness, black comedy that satirized war, consumerism, television, the music business, and most especially, the band themselves. Receiving mixed reviews, the film alienated the band’s teenage fanbase, while failing to attract the hipper, older audience the band had been striving for. Corresponding with a steep drop in the group’s popularity as recording artists, the film effectively marked the end of The Monkees phenomenon.

Undaunted, and indeed somewhat relieved, to be liberated from a show that, though it had made them rich and famous, lacked the cultural kudos they craved, Schneider and Rafelson began casting about for their next project. This came via actors Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper who had an idea for a modern western about two bikers who score a large sum of money in a drug deal and travel across the southern United States encountering hippies and rednecks along the way. Raybert agreed to produce what was then called The Loners (it was soon retitled Easy Rider by Terry Southern who turned the original idea into a screenplay). Schneider, who financed the film with his own money, agreed to let Hopper direct, despite his lack of experience and volatile reputation. Filming on location in New Orleans during Mardi Gras, this reputation proved all too warranted, as an increasingly paranoid Hopper ranted and raved, falling out with Fonda, and fighting for control of the project from a hastily organized crew.

Despite the disastrous New Orleans episode, Schneider kept faith with Hopper, ensuring that a proper crew was assembled for the rest of the shoot. The team included cinematographer Lázsló Kovács, who would become a key contributor to the look of American New Wave cinema over the coming decade, and Jack Nicholson who was hired to play hard-drinking lawyer George Hanson when Rip Torn, who had already been cast in the role, withdrew after a bitter argument with Hopper. Nicholson, who had been acting in movies for a decade but had failed to make much of an impact, was on the verge of giving it up for a career behind the camera. His performance, full of little touches that brought the character to life, turned out to be the most memorable in the film, establishing the "rebel against the system" persona he would become famous for.

Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider [1969]

|

Filming took place in the spring and early summer of 1968 in scenic locations that included Monument Valley and Louisiana, although the hippy commune featured in the film had to be recreated in Malibu, California, because the original – in Taos, New Mexico – did not permit shooting there. Nicholson helped to keep the peace between Hopper and Fonda, and the production was conducted on a more professional basis than it had been previously. As a director, Hopper broke a number of the established rules of filmmaking, improvising much of the dialogue, and ignoring mismatches of continuity.

Influenced by experimental filmmakers like his close friend Bruce Conner, Hopper continued to follow his own vision in the editing room. He refused to discard technical imperfections like lens flair, and incorporated jump cuts and flash forwards – a narrative device in which a shot from later in the story is intercut into the current scene. When Hopper’s original cut came in over 4 hours long, Bert Schneider persuaded him to take an extended holiday and brought in Henry Jaglom to edit the film down to a more coherent and commercial 95 minutes.

The Men Who Would Be Godard

Jim McBride's David Holzman's Diary [1967]

|

By the late 1960s, thousands of American students began graduating from newly-established college film courses. Many dreamed of emulating the uncompromising approach of Jean-Luc Godard and making films as a form of self-expression. Few, though, had the ingenuity and drive to succeed in the real world of film production. Among the few exceptions was Jim McBride who attended New York University film-school, but discovered his studies meant little when it came to finding employment in the industry. “There was absolutely no correlation between the education or the degree you got from film school and the real world outside,” he commented in a later interview.

Eventually McBride raised $2,500, and with cinematographer Michael Wadleigh (who would direct of Woodstock), and actor Kit Carson, made his own movie. McBride’s ingenious concept for David Holzman’s Diary, was to make a fictional film using cinema verité techniques as if it were real. In the title role, Carson plays a young filmmaker who puts Jean-Luc Godard’s dictum that “cinema is truth 24 frames per second” to the test, by pointing a camera at himself and those around him. Through this process he hopes to capture an honest record of his life. Instead his obsessive filming alienates everyone, particularly his girlfriend Penny, leaving him alone and suicidal. The film satirizes the very idea, put forward by Direct Cinema and the cinéma verité movement, that filmmakers can capture objective truth, and undermines its own premise in a scene in which David’s friend tells him: “As soon as you start filming something. Whatever happens in front of the camera is not reality anymore. It becomes something else. It becomes a movie.”

Like the early work of the French New Wave, David Holzman’s Diary (1967) showed what could be achieved by simply filming one’s immediate environment directly and without intervention. As a foretaste of the endless video diaries and reality TV of the present day, the film was remarkably prescient. Its importance was recognised by the Library of Congress when they selected it for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Brian De Palma was another East-Coast-based, young independent director working outside the mainstream. For him, as for many cinephiles living in New York, the French New Wave was a revelation. "Godard's a terrific influence, of course. If I could be the American Godard, that would be great," he said in 1969 after the unexpected success of his experimental satirical comedy Greetings (1968).

Brian De Palma's Greetings [1968]

|

Born in Philadelphia in 1940, De Palma majored in science at Columbia University before becoming interested in film and making several shorts, including the well-regarded Woton's Wake (1962). His first feature, The Wedding Party (shot in 1963, released in 1969), was a collaborative experiment financed by a wealthy fellow student that featured the screen debuts of both Robert De Niro and Jill Clayburgh, however the film failed to receive distribution. De Palma’s next movie, Murder a la Mod (1968), opened in just one cinema in Greenwich Village before disappearing.

Persevering, De Palma borrowed Jean-Luc Godard's central premise from Masculin Feminin (1966) of young people dealing with contemporary problems, and wrote the outline for what would become Greetings. Independent producer Charles Hirsh liked De Palma’s short outline and together they made the film in two weeks for a budget of $41,000.

Starring Robert De Niro, Greetings’s episodic narrative follows a trio of New Yorkers and their involvement in the Vietnam War draft, computer dating, and the conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination of President John F Kennedy. Unexpectedly, the film, whose irreverence and topicality struck a chord with younger cinemagoers, pulled in over a million dollars at the box office. Following its success, De Palma and Hirsh made a sequel, the even more experimental (and politically radical) Hi Mom! (1969). By now De Palma's reputation had reached Hollywood where he was hired to direct the Warner Brothers comedy Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972). The experience, however, was not a happy one and the film flopped. It would be some years before De Palma would break through into the mainstream, by which time it was Alfred Hitchcock rather than Godard who had become his guiding inspiration.

Martin Scorsese, a close friend of De Palma’s, was born in New York and raised in Little Italy. He grew up watching movies from a young age. “My father used to take me to see all sorts of films,” he recalled. “From three, four, five years old, I was watching film after film, a complete range.” He suffered from asthma and as a result often stayed home from school, watching Hollywood classics and European films on television or at the local movie theatre instead. After leaving high school he spent some time in a seminary training to be a priest, but was expelled for failing to concentrate on his studies. Instead he enrolled at New York University where he studied the history and aesthetics of cinema under the inspiring instruction of teacher Haig Manoogian. Here he made the comic shorts What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (1963) and It’s Not Just You, Murray (1964). After receiving his degree from NYU in 1964, Scorsese stayed on as an instructor of film technique and, at the same time, began making his first full-length feature.

Scorsese's Who's That Knocking at My Door? [1967]

|

Initially financed with a few thousand dollars from his father, Scorsese’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door? was an attempt to convey the kind of life that he and his friends lived in their Sicilian-American neighbourhood in the lower east side. Its central story revolved around the character of JR – played by Harvey Keitel, making his screen acting debut – a young Italian American man who pursues a free-spirited girl (Zina Bethune), but finds it impossible to come to terms with her secret past.

Stylistically, Scorsese was inspired by the new cinema coming out of Europe, particularly France and Italy, as he later recalled: “I was not interested in making a film that had a straight narrative structure, because at that time you have to understand all these films were opening up and they told stories in different ways.”

The film eventually took two years to make, with Scorsese and his crew shooting scenes whenever there was an opportunity to do so. The discontinuous production schedule and low budget resulted in an often-fragmented film, with frequent shifts of continuity and texture (some scenes were shot on 16mm and some on 35mm). Nevertheless Who’s That Knocking at My Door? was a promising debut that featured situations and thematic concerns Scorsese would return to repeatedly later in his career. After seeing its premiere at the 1967 Chicago Film Festival, critic Roger Ebert described the film as “a work that is absolutely genuine, artistically satisfying and technically comparable to the best films being made anywhere.” Despite this vote of confidence it would be another two years before Scorsese found a distributer for the film. In the meantime he lived hand to mouth, working on commercials in Europe and eventually making a name for himself as an editor, most notably on Woodstock (1970).

1969

1969 marked the beginning of a three year slump in cinema attendances in America to an all time low of 15.8 million a week in 1971 (by comparison attendances in 1946 were 78.2 million a week). At the same time overheads were rising. Sensing an opportunity, wealthy corporations who had made their money in industries such as zinc mining or hotels, began buying and taking over the ailing Hollywood studios. Paramount was sold to Gulf + Western industries run by Charles Bluhdorn, and MGM to Navada casino millionaire Kirk Kerkorian. An unexpectedly positive consequence of these upheavals was the arrival of new production executives such as Robert Evans at Paramount, and John Calley at Warner Brothers, whose creative judgement would play a decisive part in the movies produced during the New Hollywood era.

One studio that had always operated differently from its bigger and more powerful competitors, and who now, despite the difficult climate, found itself prospering, was United Artists. Ever since it had been set up by Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith in 1919, U.A. had put the filmmaker first and it continued to do so. In the 1960s they had made a fortune from the hugely successful James Bond pictures, the Pink Panther series, Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns and the Beatles films. They had also scored artistically, winning Best Picture Academy Awards for Tom Jones (1963) and In the Heat of the Night (1967). They would win the Best Picture Oscar again in 1970 for a groundbreaking and controversial depiction of New York street life.

Midnight Cowboy

Based on a novel by James Leo Herlihy, Midnight Cowboy had been in development for some years before going into production. Its story of Joe Buck, a young Texan dreamer, who travels to New York to make his fortune as a gigolo, but ends up down and out in the company of Ratso Rizzo, a consumptive street hustler, included frank depictions of homosexuality and drug-taking. Its director, John Schlesinger, who had helped to revitalise British cinema with New Wave classics like A Kind of Loving (1962), Billy Liar (1963), and Darling (1965), later recalled his first reaction to the book: “I read it and thought ‘If I’m going to make a film in America, then this is the one that I want to do’.” He took the book to producer Jerry Hellman, and together they approached the head of production at United Artists, David Picker, who agreed to finance the project as long as its budget was kept to a very low $1 million (this was eventually raised to $2.3 million).

Schlesinger's Midnight Cowboy [1965]

|

The screenplay went through several unsatisfactory drafts before Waldo Salt, a screenwriter who had been blacklisted in the 1950s after refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, came on board. His adaptation, in which flashbacks to Joe’s early life in Texas are incorporated into the main narrative, had exactly the mix of compassion and ironic social satire Schlesinger had been looking for. In the lead roles he cast Jon Voight as Joe, and Dustin Hoffman as Ratso, on the strength of his pre-Graduate performance in the off-Broadway production Eh?. The Graduate’s director, Mike Nichols, advised Hoffman not to play the part of Ratso, believing it would damage his new romantic leading man status. But Hoffman, who was uncomfortable with that status and longed to prove himself a real actor, relished the opportunity to take on such a contrasting role. Schlesinger’s first choice to play Joe was the already established Michael Sarrazin, but casting director Marion Dougherty, who helped launch the careers of a number of actors and actresses who would come to prominence during the New Hollywood era, kept pushing the initially reluctant Schlesinger to screen-test the then little-known Voight. Schlesinger wavered for a while, but eventually agreed that Voight had more chemistry with Hoffman and offered him the part.

Shooting on location in such contrasting settings as rural Texas and New York’s Times Square, Schlesinger and his Polish cinematographer Adam Holender captured the contemporary American landscape with a vivid authenticity rarely matched on screen before. In the lead roles, Voight and Hoffman, amply paying off Schlesinger’s faith in them, gave brilliant performances as the naïve, out-of-his-depth, Joe, and the seedy, but ultimately loveable, Ratso. The memorable supporting cast included Sylvia Miles as an aging Park Avenue kept-woman, John McGiver as a religious fanatic, and Brenda Vaccaro as the sympathetic client Joe meets at a bohemian party. Yet, in spite of the obvious quality of what he had shot, an exhausted Schlesinger was plagued with doubts about the first cut. He brought in his long-time editor, Jim Clark, as creative consultant. Clark reshaped the disparate elements: intercutting subjective flashbacks with real world footage, black and white with colour, to create an unconventional, sometimes feverish, expressionism. It was also Clark’s suggestion to put Harry Nilsson singing Everybody’s Talkin on the soundtrack, which, along with John Barry’s haunting title theme, helped to transform the emotional impact of the film.

When it went in front of the Motion Picture Association of America ratings board, Midnight Cowboy received an X-rating – the first X-rated movie released by a major studio. However early screenings were overwhelmingly positive and soon audiences were queuing up around the block to see the film. Its success was crowned at the 1970 Academy Awards where it won for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. Yet, when shooting was over, the film’s qualities had yet to be recognised and Schlesinger was exhausted and plagued with doubts about the film. His anxiety wasn’t helped when the ratings board slapped the film with an X rating – the first X-rated movie released by a studio. However early screenings were overwhelmingly positive; there was a 10-minute ovation on opening night and soon audiences were queuing up around the block to see the film. Midnight Cowboy eventually became the second highest grossing movie of 1969.

“We did it, man. We did it. We’re rich, man.”

Easy Rider finally premiered at the 1969 Cannes Festival, where the troupe of long-haired, bearded hippie filmmakers who had come to present the film caused a sensation along the Croisette. The film was well-received and won Dennis Hopper an award for Best First Work – an prize created especially so that the film could be honored. When it opened in America later that summer it was greeted with grateful recognition by a counter-culture who were unaccustomed to seeing themselves and their beliefs portrayed on screen. Fuelled by an exceptional rock soundtrack, featuring Steppenwolf, The Band, The Byrds and Jimi Hendrix, the film became a major box-office hit, going onto earn more than $60 million worldwide. It even received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor (Jack Nicholson).

In one of Easy Rider’s final scenes, Wyatt tells Billy: “We blew it.” He might have been speaking for the whole country. The idealism and sense of possibility that had characterised much of the 1960s had, by the end of the decade, given way to anger and confrontation. In 1968 there were the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the escalation of the Vietnam war, and race riots in a number of major cities, including Chicago and Washington, D.C. Across the country younger people were rejecting the values of their parents. This divide was very apparent at the 1970 Academy Awards where New Hollywood films like Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider, which had re-contextualised Western iconography in a contemporary setting, competed for awards with more traditional examples of the genre like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and True Grit.

“If they move… kill ‘em!”

William Holden in Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch [1969]

|

Another nominee at the 1970 Academy Awards (for Best Original Screenplay and Best Original Score), Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch was a different kind of Western altogether. Set in the dying days of the Old West, it follows the misadventures of a gang of outlaws led by Pike Bishop (William Holden), who flee to Mexico following a botched bank robbery pursued by Bishop’s former partner Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), and a posse of men hired by the railroad. There they get caught up in the Mexican revolution resulting in a bloody showdown with a renegade General and his ragtag army of Mexican Federale soldiers.

The Wild Bunch portrayed American history at its most brutal and many critics condemned the film’s graphic violence. Peckinpah argued that it showed the violence of the West, and the character of the men who perpetrated it, authentically and realistically for the first time. He also claimed it was an intentional allegory of the war in Vietnam, whose carnage was then being televised nightly in American homes on the evening news. Whatever his intention, nobody could deny Peckinpah’s brilliant and ground-breaking use of technique in The Wild Bunch. Intercutting shots from multiple angles, slowing down and speeding up action, he brought a new level of artistry to the filming of action sequences that would prove highly influential.

Combative and uncompromising, Sam Peckinpah was not afraid of upsetting either studio executives, or crewmembers, when it came to realising his vision on screen. A brilliant craftsman with a poetic sensibility, he had made his name in the late 1950s writing and directing television shows like The Rifleman and The Westerner. His second cinema feature Ride the High Country was popular in Europe where it was hailed as a brilliant reworking of the Western genre. American critics praised it too, with Newsweek magazine naming it the best film of the year. Peckinpah’s follow up, Major Dundee, however, went over-budget and over-schedule, and was taken away from its director and substantially re-edited. The resulting muddle failed at the box office, and Peckinpah was subsequently fired from his next film The Cincinnati Kid when its producer heard that he was difficult to work with.

Effectively ostracised for several years, Peckinpah survived as a screenwriter. By the time he returned to directing in the late 1960s, the cinematic landscape had changed. Bonnie and Clyde, in particular, had widened the parameters of what was acceptable for a mainstream American movie. When The Wild Bunch became a hit for Warner Bros., Peckinpah’s immediate future as a director was ensured. Over the next decade and a half his name became synonymous with violence and controversy, but to younger New Hollywood acolytes like Paul Schrader and John Milius, he was a maverick genius who refused to kowtow to the system. His anti-establishment stance was reflected in many of the protagonists of his movies: talented men hired for a job who find themselves double-crossed and outgunned, but hold steady to a code of honor, even if it means their own self-destruction. Inevitably, Peckinpah’s hard-living lifestyle, which included years of alcohol and cocaine abuse, caught up with him, and he died at the age of 59 in 1984.

Communities Of Outsiders

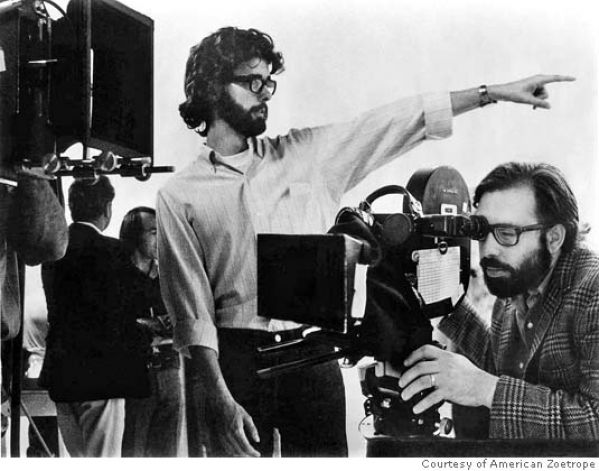

Like Sam Peckinpah before him, Francis Ford Coppola was discovering what it felt like to have his artistic vision opposed by studio executives. Hired by Warner Brothers to direct the film version of the Broadway musical Finian’s Rainbow staring Fred Astaire and Petula Clark, Coppola wanted to make it as realistic as possible. He built outdoor sets on location in the Napa Valley and wanted to stage most of the action there. The studio preferred the film to be made in the controlled environment of Hollywood soundstages and the studio backlot. Eventually they reached a compromise – both locations were used, but the results were uneven and did little to enhance Coppola’s reputation. Released in 1968, Finian’s Rainbow received mixed reviews and failed to fulfil expectations at the box-office. Its making did, however, introduce Coppola to a young film student who had won an award that allowed him to spend time observing a Warner Brothers film in production. The friendship that began on set between the intense, shy student, George Lucas, and the swaggering, ebullient Coppola, would have a momentous effect on the future course of cinema.

George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola

|

After the frustration of making Finian’s Rainbow, Coppola was determined that his next film would be smaller-scale and more personal. With this in mind, he wrote an original screenplay, The Rain People, based on an incident from his own childhood when his mother disappeared from the family home for a number of days. Unwilling to wait for Studio approval, Coppola initially financed the film himself (using his fee from Finian’s Rainbow), taking off on the road with a small crew that included George Lucas as production assistant and chronicler (he would direct a 30 minute documentary about the production called Filmmaker). Amongst the cast were Shirley Knight as the female lead who leaves her husband and sets off on a journey of discovery, and James Caan and Robert Duval as two lost souls she meets along the way.

Taking advantage of the visual opportunities presented by the American landscape, and equipped with the latest, lightweight equipment, Coppola and his team shot and edited the film on location. Reckless though it may have seemed to some, Coppola’s cinematic adventure, artistically at least, paid off, resulting in his most accomplished film so far. The experience convinced him that movies no longer had to be made in Hollywood, and that he worked best amongst a community of like-minded collaborators. Coppola decided, with Lucas, to set up a studio that would build on this realisation, producing more personal films, as well as giving aspiring filmmakers their chance to direct. “It was,” Lucas later explained, “a way of saying we don’t want to be part of the Establishment, we don’t want to make their kind of movies, we want to make something completely different.” To help achieve this, Coppola and Lucas’s first decision was to move their base of operation away from the traditional industry powerbase of LA up the coast to San Francisco where they set up their new company called American Zoetrope in an old warehouse. Here they installed editing suites, space for an art department, wardrobe, props, and sound dubbing. Crucially, Coppola was able to persuade John Calley, head of production at Warner Brothers, to back the new venture with $300,000. Much of this went toward the development of screenplays by former USC and UCLA film student friends of Coppola and Lucas, like Willard Huyck, Carroll Ballard, Matthew Robbins, Hal Barwood, and others. First into production would be Lucas’s debut feature – a dystopian science fiction story called THX 1138.

Arlo Guthrie in Arthur Penn's Alice's Restaurant [1969]

|

American Zoetrope was just one of many alternative, idealistic communities then springing up across America inspired by hippie idealism. Director, Arthur Penn, explored the phenomenon in Alice’s Restaurant, based on the satirical song of the same name by folk troubadour, Arlo Guthrie. In the film, Arlo, playing himself, is a student hoping for a way to avoid the draft. He takes up residence in a deconsecrated church in Massachusetts with older friends Alice and Ray, as well as other like-minded bohemian types. After Thanksgiving dinner he decides to do his hosts a favour by getting rid of their garbage by taking it to the town dump. When he finds it closed, he throws the garbage instead on top of another pile he finds at the bottom of a cliff. This lands him in trouble with the local police who arrest him. The criminal conviction unexpectedly results in him being rejected for military service in Vietnam. Warm and whimsical at first, the movie takes a darker turn when one member of the community overdoses on heroin. In the film’s final shot, Alice gazes pensively toward the camera as she contemplates an uncertain future. It’s a haunting moment that suggests the fragility and contradictions inherent in the carefree, counter-culture lifestyle.

Peace, Love and Murder

The opposing Aquarian and Saturnalian tendencies of the burgeoning hippie movement were played out for real in the summer of 1969. Over a long weekend, between August 15th and August 18th, 500,000 concert-goers descended on Woodstock, New York, to enjoy, “3 Days of Peace and Music.” A watershed moment that defined a generation, the Woodstock Festival brought together half a million people united in a message of peace, openness and community. Meanwhile, just days before, on the other side of America in Los Angeles, members of a quasi-commune lead by aspiring rock-star Charles Manson, broke into the rented home of Roman Polanski, who was away in Europe at the time, and murdered his wife, Sharon Tate, their unborn child, and three others. The next night, “the Manson family” – as they were known – murdered two more people. This was the hippie dream turned nightmare – members of their own community unleashing an orgy of rage and violence fuelled by drugs and warped conspiracy theories.

“Look out Haskell, it’s real!”

Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool [1969]

|

In reality, while the children of the middle-classes were “turning on, tuning in and dropping out,” many Americans were simply battling to survive. Whether in the jungles of Vietnam, or the inner city ghettos, life for them did not resemble the idealised life-styles portrayed in many television shows and Hollywood movies. Acclaimed cinematographer turned director, Haskell Wexler, was determined to depict life as so many experienced it. In an interview in 1968, he stated that he wanted to “find some wedding between features and cinema-verité.” In its mix of documentary and fictional narrative, his remarkable debut feature, Medium Cool (1969), achieved just that.

The film’s protagonist is a Chicago television news cameraman played by Robert Forster, who, at first, appears oblivious of the responsibilities of his profession. “Jesus, I love to shoot film,” he proclaims after filming the aftermath of a car crash. But the discovery that his boss has been showing out-takes of his work, including footage of radical groups, to the FBI, sparks a growing awareness of his own responsibility. At the same time he becomes involved with Eileen, whose husband has died in Vietnam, and her son Harold. The film climaxes with Eileen desperately searching for Harold who has gone missing amongst the crowds of protestors and police at the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention. Wexler and his crew filmed these scenes during the actual protest and the ensuing riot. At one point a tear-gas canister comes flying toward the camera as a voice off-screen exclaims: “Look out Haskell, it’s real!” Though unintentional, the line crystallizes perfectly the film’s exploration of fact vs. fiction and the thin line that often separates the two.

Return to: 'American New Wave' home. |